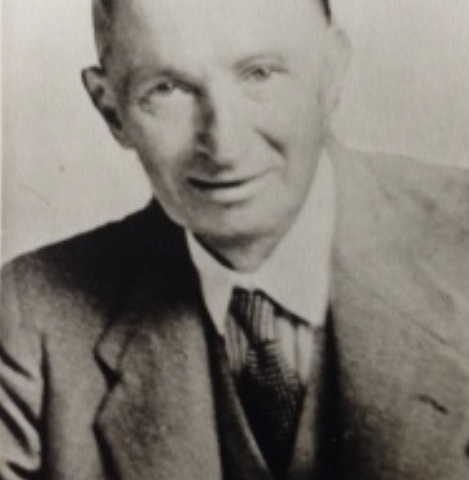

Richard FRY the younger (1816-1899), was not my direct ancestor, however he was the only son of my direct ancestor Richard FRY (1780-1855) and a fascinating character.

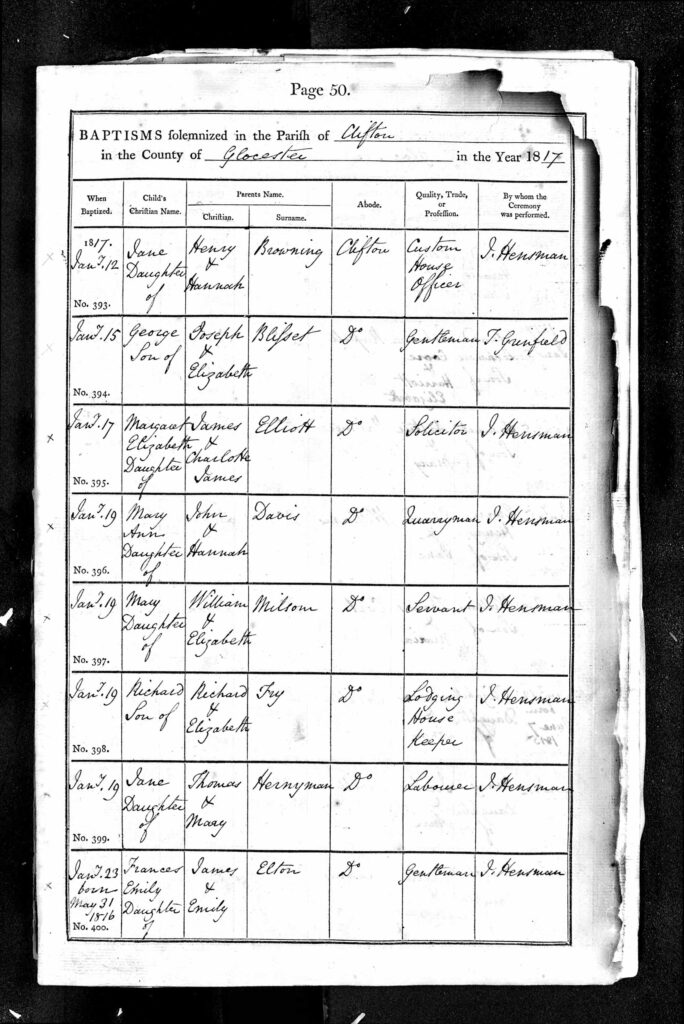

He was born at a Lodging House in Sion Row, Clifton, near Bristol, on Christmas Eve, 24th December 1816. His parents Richard FRY and Elizabeth FRY (nee MAIDEN) were lodging house keepers there, and they had spent the first nine years of their marriage childless, before having a daughter, Elizabeth FRY in 1813, and then finally, in 1816, having their much-longed for son.

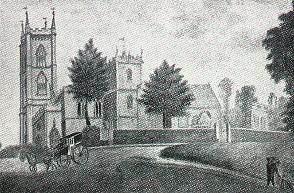

Richard was baptised just after New Year, on 7th January 1819 in the parish church of St Andrew’s Clifton.

In 1818, when Richard was just two years old, his father moved the family to Weston-super-Mare so he could take over the running of the Hotel there. Therefore, Richard had an interesting early childhood, growing up in the relative grandeur of the surroundings of the Hotel in what was previously just a coastal village, but which the FRY family believed could become a fashionable resource due to the increased interest in sea-bathing. Richard’s childhood therefore would have been quite privileged and also he’d have had plenty of access to play by the sea with his sister, which may have ignited within them both a love of the sea and in Richard, perhaps a great desire to set sail.

Richard’s family moved into Myrtle Cottage next door to the Hotel at some stage, but by this time, Richard had already been sent away to be educated as it’s known that he attended boarding school in Yatton at Rockhouse Academy. He then did his apprenticeship in Yatton too, to become a Carpenter and finally he moved to Bristol where he worked for around 4 years.

At some point, he returned home to Weston. In 1832, his elder sister Elizabeth married Joseph JAMES a local carpenter and builder in Weston who came to live with the family at Myrtle Cottage. Shortly after this, Richard’s father, Richard the senior, began a building project on their land, just next door to their home, to build the second hotel in Weston. It seems likely that Richard the younger might have helped with the building on the site, perhaps under the direction and supervision of Joseph JAMES his brother-in-law, but he may also have been working independently in Bristol.

At the age of 22, the census records that Richard was living at home with his parents at Myrtle Cottage. At this time, his father was a very successful local figure who was heavily involved with both the local development of the area and the local church.

Evidently, as a young bachelor, Richard did not find anyone locally who he wished to marry, and it seems that he may have longed for adventure and exploration. Perhaps he still dreamed of sailing away across the open seas.

A Voyage to New Zealand

Richard would most likely have heard about the growing settlements on the other side of the world in New Zealand and through propaganda and advertising promoted by the Otago Association, an off shoot of The New Zealand Company.

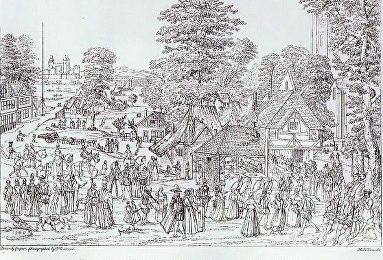

The New Zealand Company tried to attract settlers from Britain by publishing romanticised images of New Zealand. A major source of this propaganda was Edward Jerningham Wakefield’s book, Adventure in New Zealand, published in London in 1845. It contained many coloured lithographs. This one, from a drawing by William Mein Smith, the first New Zealand Company surveyor general, shows the company settlement of Petre (Whanganui) in September 1841.

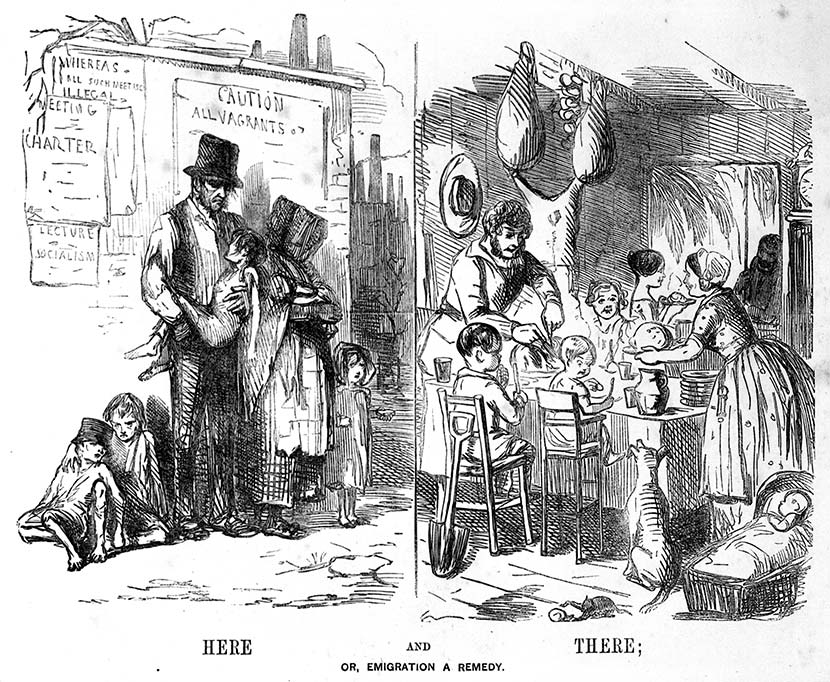

This famous emigration poster compares life in England and New Zealand. In the 1830s and 1840s many people in England believed in the theory that population growth was related to food production, and that as Britain’s population continued to rise there would be penury and starvation – as depicted in the scene on the left. The solution was to encourage emigration to countries where abundant land would bring plenty of food and health – as in the happy scene on the right.

By 1839 there were only about 2,000 immigrants in New Zealand in total; but by 1852 there would be a population of 28,000 immigrants as people flocked to settle there. What led to this remarkable change was the Treaty of Waitangi which was signed in 1840. This established British authority (in European eyes) and gave British immigrants legal rights there as citizens. The treaty helped ensure that for the next century and beyond, most immigrants to New Zealand would come from the United Kingdom and in 1840 the first immigrants assisted by the ‘New Zealand Company’ arrived. Perhaps this development ignited Richard’s passions and thirst for adventure, because a few years later he hatch a plan to leave Weston-super-Mare for good, and take a lengthy voyage to settle in New Zealand.

In 1847, when Richard was by now 30 years of age, still unmarried, he made a life-changing decision. His parents were now elderly. His Father was 66 and his mother 71. His older sister Elizabeth was now 33 and happily settled with her husband Joseph JAMES and their rapidly growing family over on Knightstone where they had moved to run the Bath House there. Richard may have felt that his life in Weston held little promise because he decided to make an ardous journey and leave his family behind him to set sail for New Zealand.

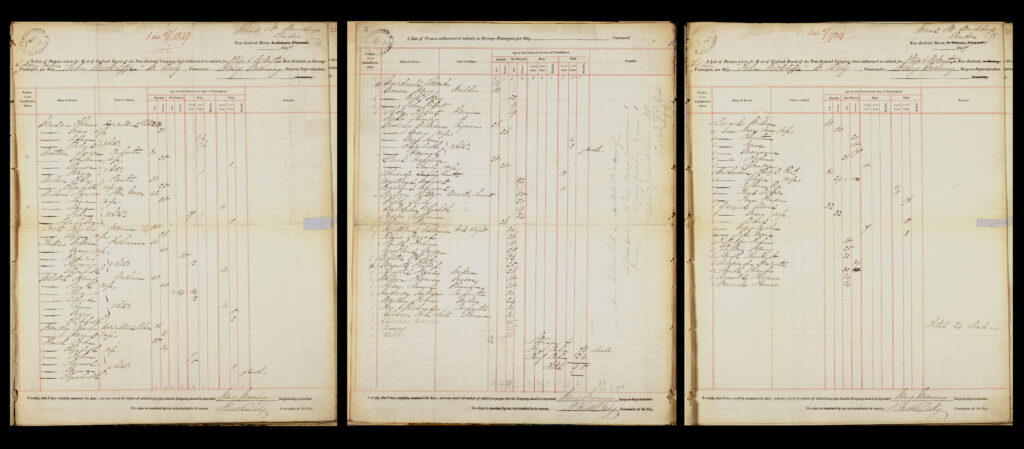

In November 1847, he travelled to Gravesend, a port near London, and on 22nd November 1847, he boarded the ‘John Wickliffe’ ship and set sail.

The JOHN WICKLIFFE was a 662 ton ship which sailed from Gravesend on 22nd November 1847, suffered some initial rough weather and conditions and hence it was delayed and then left Portsmouth on 14th December 1847, and finally it arrived at Port Chalmers, New Zealand, on 23rd March 1848. Bartholomew Daly was the Commander and a Dr Henry Manning, was the surgeon on board. The voyage was very long and he spent almost four months at sea!

Historic Account of the John Wickliffe Voyage

The following is an account and history of the voyage by Professor Tony Ballantyne from the University of Otago:

“The John Wickliffe, a 662-ton vessel which functioned as the Otago Association’s storeship but also carried 97 passengers, arrived at Kōpūtai or Port Chalmers on 23 March 1848. Its passengers were pleased that its passage was a neat 100 days: but this figure was only accurate if this calculation was made from 14 December, the date it sailed from Portsmouth. In fact, the John Wickliffe originally departed from Gravesend on 24 November 1847, but inclement weather and contrary winds thwarted its early progress and it took almost three weeks until it finally made positive progress. (In a later blog post we will explore the nature of the voyage itself and also the history of the Philip Laing which arrived 24 days later on 15 April 1848.)

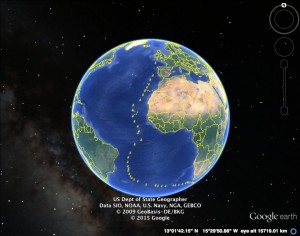

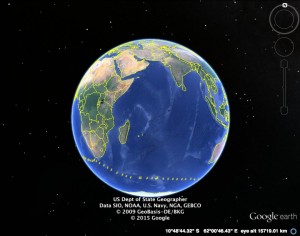

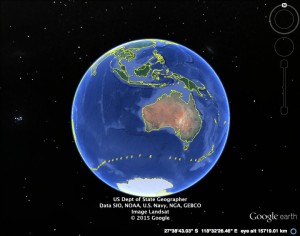

The track of the John Wickliffe, based on Rev. T. D. Nicholson’s Journal.

By the time John Wickliffe was quickly pushing east to the south of Australia, its crew and passengers were looking forward to sighting the land that was to be their new home. On 15 March, the Rev. T. D. Nicholson, who subsequently became an influential figure in the early history of Presbyterianism in Nelson, wrote in his journal: ‘A few days more, and a very few, and God’s Arm of safety around us, and the long sought shores of Otago shall see us.’ On March 18, the passengers began preparing a special banner to mark their landing at Otago: it was fashioned out of Mrs Nicholson’s wedding dress of ‘silk so blue’. On March 19, excitement rose as passengers saw the Snares Islands and then Rakiura/Stewart Island and on the 20th, the John Wickliffe sailed pass the mouth of the Mata-au or Clutha river. The wind dropped on the 21st and progress was slow along the coast. Onboard the John Wickliffe, Thomas Ferens, a Methodist dispatched to assist Charles Creed’s missionary work at Waikouaiti, was impressed by ‘Saddle Back Hill’ and noted ‘there are some very striking land marks’. The day’s slow progress left the eager colonists sitting some 6 miles from Cape Saunders. Ferens observed the abundant wildlife: ‘Birds of all descriptions are here – Gulls, Whale Birds, Sea Pigeons, Albatrosses, Cormorants’. He also suggested that the ‘air is most delightful – a sultry, ethereal sky, quite of the Italian character.’ His journal entry concluded: ‘Oh, what restlessness and anxiety to gain anchorages, and be on shore.’

On the 22nd the John Wickliffe anchored at the entrance to Harbour. The gunshots that captain had been routinely ordering as the vessel progressed along the coast finally had some result, as Charles Kettle, the New Zealand Company surveyor, and Richard Driver, the pilot, brought boats out to the John Wickliffe’s anchorage. Unfavourable winds prevented the vessel entering the harbour proper, but some of the passengers used this time to good effect. Henry Monson, an English Methodist colonist who would eventually become Dunedin’s gaoler, his second son John, and Thomas Ferens went out in a one of the John Wickliffe’s small boats with three Kāi Tahu men: they went ‘a-fishing Beracootas by a long pole with a short piece of wood and a crooked nail at the end which is attached with a string to the pole in the water’. This party landed three fish. Other passengers ventured out with another party of Kāi Tahu, headed by the great chief Te Matenga Taiaroa. These engagements initiated a tradition of collaboration and reciprocity that would not always endure. Ferens observed that these Kāi Tahu who welcomed the colonists were ‘very peaceful intelligent men’.

For March 23rd, the day the passengers finally arrived on land, Ferens began his journal with the simple but powerful observation: ‘A great day.’ But the landing itself was quite uncoordinated: Reverend Nicholson recorded:

The landing was neither particular nor general – one boat with a party went up to Dunedin, and separate parties went ashore at Port Chalmers to spy the land – all seemed pleased and called it a goodly land – Port Chalmers and around is truly beautiful – rich in scenery – its slopes and shores are fertile, and wooded to the water’s edge.

Ferens was also struck by the new environment: it seemed that he was encountering ‘nature triumphant’ and the beauty of the harbour was such that it made ‘the mind to rejoice and adore the Divine Being.’ Ferens went ashore with a party of other passengers and explored the bush-clad hills. The party shared a meal of fish and kumara with two Kāi Tahu before ascending the hill. The party ‘rambled amongst the Suple Jacks, a description of cane, underwood, numerous Cabbage Trees, Ferns Trees, Shrub plants, Brambles – the pines are noble trees, and many others of excellent size and quality.’ Ferens was particularly struck by the

Birds of various species – Thrushes, Green and Gray, Robin with white breasts and brown back and head – Linnets, Buntings, Tui, the Mocking Bird of the Starling species – 2 white tufts under the bill, and grey feathers on the neck – Cannaries – Cacaus [kākā] or the large Parrots, Parroquete – Pigeons plentiful and numerous.

The arrival of the John Wickliffe not only laid the foundations of the permanent colonisation of Otago, but it also marked a key turning point in the transformation of the local environment: this world of trees and birds quickly came under pressure. In later posts, we will reflect on some of those changes as well as exploring the development of the colony over the following decades.“

Kettle, Charles Henry, 1821-1862. Kettle, Charles Henry 1820-1862: View of Port Chalmers and the Islands, Otakou Harbour, taken from the water May 1848. Ref: C-012-002. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22878087

Thomas Ferens Diaries On Board

In a publication called “WHITE WINGS VOL II. FOUNDING OF THE PROVINCES AND OLD-TIME SHIPPING. PASSENGER SHIPS FROM 1840 TO 1885” it is explained that Mr. Thomas Ferens, who was a passenger by the John Wickliffe, kept a diary on board.

“Mr. Thomas Ferens was born at West Rainton, Durham, and died at Oamaru in 1888, aged 65 years. He writes:—”We weighed anchor at Gravesend on November 24, but had to anchor in the Downs, where a most tempestuous night was spent with fears of a lee shore. We made another start on the 28th, but were driven back a second time to the Downs. Eventually we sailed on December 4, 1847, but soon encountered another severe gale which drove us to St. Helen’s (Isle of Wight). On December 14 we made another start, and had a hard tussle to clear the English Channel, the passengers spending many distressing days while passing through the English and St. George’s Channels.”

“Mr. J. Harries was first mate, Mr. Renalls second, and Mr. Moffatt third. During a heavy gale when the ship entered the Atlantic, Mr. Moffatt fell overboard, but fortunately seized a rope in his fall and was brought on board. The ship was then favoured with good weather and logged her ten and twelve knots.”

“The Equator was crossed on January 15, and the next day we were favoured with fresh S.E. trade winds, which were delightful. The tropical winds continued until January 26. The weather continued warm and pleasant until February 12, when a severe gale sprang up and heavy seas broke on board, but with a fair wind we were making from ten to eleven knots, two days later twelve knots, and on the 18th we made 14 knots.”

“During the next two days we passed three very large icebergs. The passengers were greatly nervous and excited at this time, and when the ship was in 49 degrees S. latitude the captain altered the course, the ship still bowling along at eleven and twelve knots with a strong wind. Bad weather set in on February 23, and continued for 48 hours, when Desolation Island was sighted. After two days of dense fog and calm, we encountered another tempestuous gale, high seas frequently breaking on board.”

“On March the ship’s position was latitude 50° 29′ S. and longitude 96° 46′ E. Very cold, hazy and stormy weather continued until March 10, with heavy seas. The Snares were sighted on March 19, and Stewart Island the following day. A steady breeze carried the ship towards the Otago Peninsula, and we sailed into port on March 23.”The best account of the ships that I have come across is to be found in Hocken’s book, “The Early History of New Zealand,” in which there is much valuable information for those who like delving into the past and tracing the steps by which the colony grew up. He mentions at the outset that Mr. John Sands, of Greenock, who owned the John Wickliffe, got £2000 for the charter, and Messrs. Laing and Ridley, of Liverpool, who owned the Philip Laing, got something over £1800. Passage money varied from 35 guineas toPAGE BREAK“

OTAGO’S FIRST IMMIGRANT SHIPS. PAGE 81 60 guineas for the cabin, 20 guineas for the fore-cabin, and 16 guineas for the steerage, or first, second, and third, as we would say nowadays.

Richard FRY arrives in New Zealand

Eventually, Richard reached New Zealand and disembarked at Port Chalmers, which was just north of Dunedin, Otago, in the south part of the South Island.

Otago celebrates the arrival of the immigrant ship John Wickliffe as the founding day of the province.

Richard’s Life in New Zealand

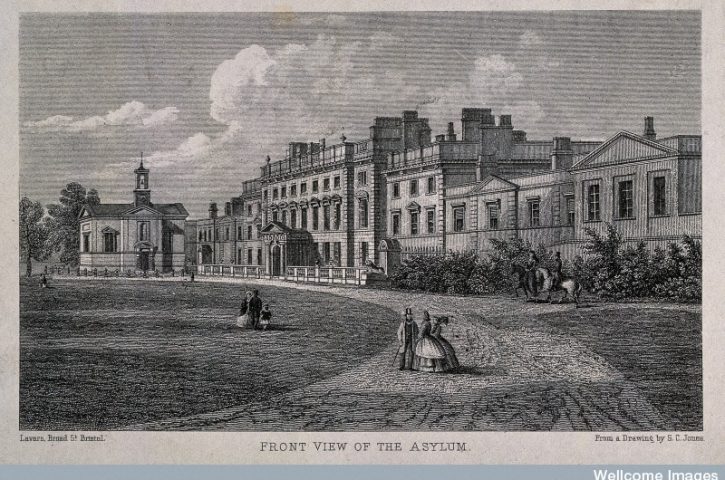

In 1840, Britain formally annexed the islands and established New Zealand’s first permanent European settlement at Wellington. That year, the Maori signed the Treaty of Waitangi, by which they recognized British sovereignty in exchange for guaranteed possession of their land. However, armed territorial conflict between the Maori and white settlers continued until 1870, when there were few Maori left to resist the European encroachment.

Originally part of the Australian colony of New South Wales, New Zealand became a separate colony in 1841.

When Richard arrived in New Zealand in 1847, he quickly established himself as a carpenter and builder. He was initially engaged to build two houses that were being erected by a Mr GARRICK (a local lawyer). One of these was erected at the corner of Jetty and Princes streets, and was occupied by Mr W. H. CUTTEN as a printing office in later years. The other building was a large framed house, which was erected at the corner of Princes street and Rattray street, and this was afterwards known as the ‘Royal Hotel’ which was perhaps reminiscent of the hotel back in the UK at Weston-super-Mare. The Royal Hotel was kept by a Mr MCDONALD, who had been another passenger on the John Wickliffe.

New Zealand became self-governing in 1852. Richard Fry was engaged by Mr John JONES to work at his settlement at Waikouaiti, and he remained in his employment for some 17 or 18 years, building cottages on the gentleman’s estate from Morrison’s at Coal Creek to Cherry Farm. He also did all the carpentry work necessary at homesteads. Richard was therefore somewhat instrumental in the original local settlement process of what would later become the huge and influential city of Dunedin.

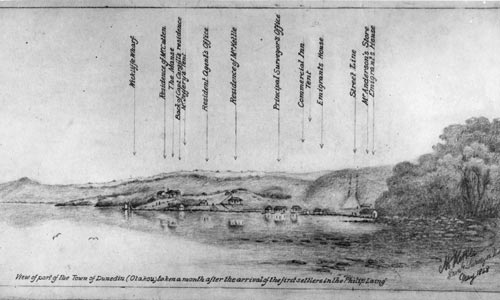

In May 1848, just over a month after the first colonist ships arrived, surveyor Charles Kettle sketched the new settlement. He identified the important official buildings and some private houses.

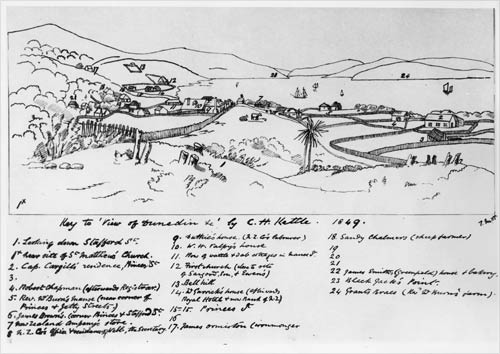

Charles Kettle’s 1849 sketch shows how much the town had developed in a year. Looking in the opposite direction to his 1848 drawing, it includes a cluster of houses, a substantial dwelling belonging to wealthy colonist W. H. Valpy, and the original First Church building.

Life in Dunedin

In an account from 1890 (entitled Picturesque Dunedin) early settlement life was described “In those early days of the settlement every man, if he intended to become prosperous, required to make himself a kind of “Jack of all trades.” He was compelled to understand a little of bush carpentering, be competent to build a sod chimney, and be able to manufacture his own furniture, before he could make himself even tolerably comfortable in his hut. He, or his wife, if he was blessed with one, would have to repair all the clothes, and also put a patch on a boot when necessary, or he would probably find himself bare-footed.“

“Many other little offices, which are so much more conveniently arranged in the Dunedin of the present day had all to be performed as “home industries” in those early days, when a pig-hunter’s hut was the only building where High street now runs, and the waves of the Bay washed over the present site of the Colonial Bank. And yet that time is less than fifty years ago. A man need not have arrived at the threescore and ten years of the Psalmist to have a recollection of that period.”

A further, comprehensive, history of Dunedin by James MacIndoe, with several mentions of Mr John Jones who Richard Fry worked with for many years can be found HERE.

Historic records for the area claim that, unlike the settlement of the rest of New Zealand, Dunedin was mostly founded by the Scottish Free Church in 1848. The city was originally to have been called New Edinburgh, and the name ‘Dunedin’ is derived from the old Gaelic name for the same city. Hence, shortly after Richard arrived in Dunedin, he must have been joined there by a whole community of Scotts!

Richard FRY Marries

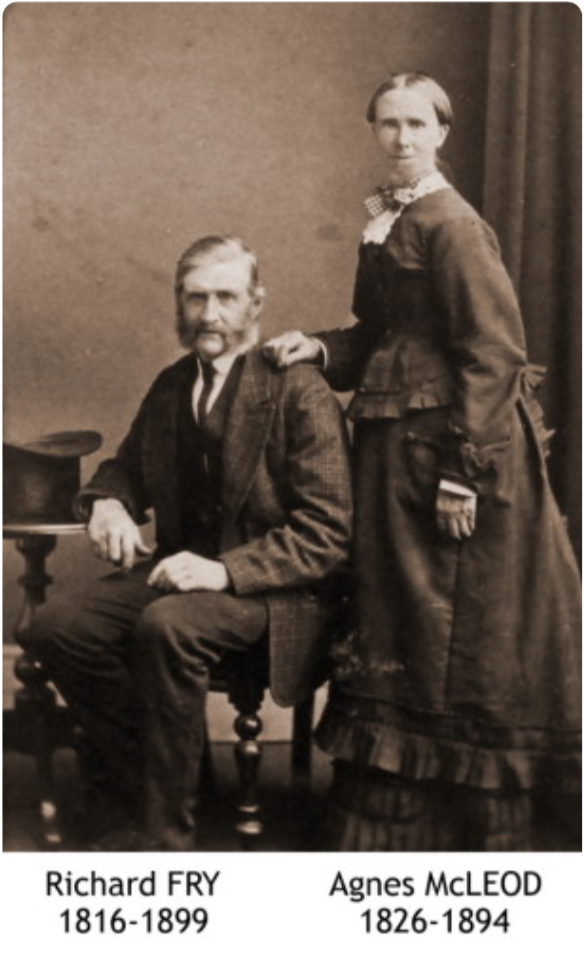

Within the first couple of years of arriving in New Zealand, it seems that Richard met one particular young Scot who left quite an impression on him because on 23rd March 1850, at the relatively older age of 34, he married a young Scottish woman named Agnes McLeod who had emigrated to New Zealand from Edinburgh, a short time after Richard Fry had arrived there. They married at Gavin Park in Manse Street in Dunedin by the Rev. Thomas Burns.

Nine months later, on 4th January 1851 in Waikouaiti, Otago, the couple welcomed their first child into the world, a son. They named him George Richard FRY, most likely after Agnes’ father (most likely George McLeod) and Richard’s father, Richard FRY.

Richard and Agnes went on to have a family of two sons and three daughters and Agnes became well known for her hospitality to travellers to the North. The family’s house was on the old track to Oamaru, and many a travellers received kind hospitality that the couple were always ready to bestow. Richard must have chosen a wife who in common some of the hospitality skills with his mother Elizabeth FRY.

Richard’s Religious and Community Interests

Richard was a P.G. of the Manchester Unity Order of Oddfellows, and he was one of the founders of the order in Otago. He met with three or four other Oddfellows in Dunedin, and he then obtained permission to open a lodge in the settlement. This was done at a meeting in the old Commercial Hotel, and the new lodge was named the Hand and Heart which later became one of the most flourishing lodges in the southern hemisphere.

Local Life in Dunedin

In 1861 gold was discovered nearby to Dunedin, and the consequential gold rush led to a great influx of population and trade. With a booming economy Dunedin soon became New Zealand’s biggest and wealthiest city.

Dunedin is full of colonial firsts, such as New Zealand’s first Botanic Garden, established in 1863. It set a trend for public gardens around the country and was recognised as a Garden of International Significance in 2010. The University of Otago, New Zealand’s oldest and most beautiful university, was set up in 1869, whilst New Zealand’s first frozen meat export left Port Chalmers in 1882, an industry that is now one of New Zealand’s biggest.

Tragedy Strikes

In the couple’s later years, Richard suffered from poor health and became an invalid, while his wife Agnes was deaf. Very sadly, Agnes who had been taking care of her husband, was one day killed in a terrible accident in town on 23rd November 1894.

Richard FRY’s Death in 1899

When Richard himself died five years later, on 9th April 1899, his obituary provided a good overview of his life and times.

Resources

The John Wickliffe’s passenger list available through Archives New Zealand.

Transcript of journal of Thomas Ferens on the ‘John Wickliffe’ and in early Dunedin, MS-0440/016, Hocken Collections.

Transcript of journal kept by Thomas Dickson Nicholson on the ‘John Wickliffe’, MS-0440/012, Hocken Collections.

Passenger List for the John Wickcliffe voyage to New Zealand (obtained from http://www.ngaiopress.com/wicklist.htm)

Aitken, George [labourer].

Alexander, Henrietta [governess to Mr Garrick’s family].

Anderson, Andrew (38) [carpenter].

Atkinson, Edward Bland (23) [storekeeper, farmer, m. Margaret Westland; Oamaru].

Batchelor, Elizabeth Wild (17) [servant; m. William Henry Monson (ex John Wickliffe); d. 9/9/1862].

Bentley, Charles (26) [miller; d. 4/12/1896]; Harriet née Ragg, wife (21) [d. 7/12/1881].

Bentley, John (24) [labourer].

Blatch, Henry Frederick (40) [gardener; Upper Harbour; d. 6/2/1888]; Sarah Mercy née Batchelor, wife (40) [d. 27/12/1886]; Thomas H (14) [d. 1/11/1925]; Alfred (12) [farmer; d. 29/6/1918]; Ann Caroline (10); Mary Eliza (4) [m. Conrad Rains (ex John Wickliffe); d. 16/10/1885]; Emma (2) [unm.; d. 30/8/1867].

Brebner, Thomas (29) [labourer, waterman; Port Chalmers; d.4/4/1883]; Mary née Hambleton, wife (23) [d. 7/1898]; Adam Glendinning (3.5) [Stationmaster at Bluff d. 10/11/1910]; Robert (1.5) [drowned Martins Bay; unm.].

Carberry, Kitty (45) [servant to Cargill family; d. 12/7/1868].

Cargill, William, Capt. (63) [leader of the Otago Settlement; d. 6/8/1860]; Mary Ann née Yates, wife (57); Christiana Dorothea (20) [m. William Henry Cutten (ex John Wickliffe); d. 24/9/1918]; Marion Jamieson (18) [m. John Rbt. Johnston]; John [m. Sarah Jones; 2nd Eliza C Featherston; runholder; in British Columbia; d. 2/1/1898], Spencer (17) [m. Mary Batson; went to India]; Annie Cunningham (13) [m. John Hyde Harris, ex Poictiers; d. 18/1/1881].

Chrystal, Francis (26) [baker, farmer; Akatore; never married; d. 1893].

Cook, Charles John (38) [mariner]; Eliza H née ?, wife (38).

Cutten, William Henry [m. Christiana Dorothea née Cargill (ex John Wickliffe); d. 30/6/1883].

Delaire, Phillip (32)

Derry or Derby, Fanny (30) [servant].

Dommett, Henry (25), labourer.

Ferens, Thomas (25) [ag. m. Margaret Westland; Oamaru; d. 6/6/1888].

Finch, John (34) [gardener, farmer; Milton; d. 22/11/1897]; Elizabeth née Shaw, wife (30) [d. 19/10/1875]; John (6) [m. Margaret Strain (ex Ajax); d. 24/1/1921]; Samuel (4) [carter, ag.; N E Valley; d. 28/2/1899]; Emma (3 [d. 26/1/1916); Elizabeth (4 months; [m William James Titchener 7/5/74; d.11/4/1927].

Fry, Richard (30) [carpenter, farmer; m. Agnes McLeod (ex Mary); Waikouaiti; d. 9/4/1899].

Garrick, David, solicitor [Sydney 1852]; Mary, wife; Caroline (8); David (6); Jessie (4); William Henry [auctioneer; Anderson’s Bay].Gibson,John Scott, (30)

Jeffreys, Julius [landowner; d. Auckland pre 1898]; Emily née ?, wife [d. 7/4/1909].

Lovell, Napoleon (28); Emily née ?, wife (28); and niece.

McDonald, Alexander (50) (alias Sinclair) [kept Royal Hotel, farmer].

Manning, Henry Dr [doctor; m. Elizabeth Stokes (ex John Wickliffe); d. 3/12/1884].

Monson, Henry (53) [carpenter, gaoler, solo father; d. 9/12/1866]; William Henry (22) [carpenter m. Elizabeth Wild née Batchelor (ex John Wickliffe); d. Eng. 1895]; John Robert (19) [Custom House officer; m. Mary Ann Roebuck; Port Chalmers d. 10/3/1914].

Mosley, William Alfred (26) [machinist, farmer; Inch Clutha; d. 25/10/1889]; Mary née Howsley, wife (26); Mary Ann (4) [d. 1893]; Elizabeth Charlotte (3) [d. 26/6/1932]; Hannah Martha (8 months) [never married].

Pike, Lucy (20), servant.

Rains, Conrad Williams Bingham (26) [labourer; m Mary Eliza née Blatch (ex John Wickliffe); d. 14/4/1877].

Shaw, Samuel (28) [painter].

Sidey, Robert Kay (19) [farmer; d. Sydney, 19/8/1916].

Smith, John Edmund (20) [clerk, ag., Factor Church Trustees; m. Matilda Trumble (ex Mariner 2nd voyage); d 13/6/1895.].

Stokes, Eliza [m. Dr Henry Manning (ex John Wickliffe)].

Taylor, Catherine (23) [servant to W Garrick].

Watson, George (30) [smith]; Susannah née ?, wife (25); Louisa (3); Henry (1).

Webb, Charles (18), [clerk to Capt. Cargill; m. Mary Anne née Graham (ex Blundell); Wellington].

Westland, William (31) [millwright; unm. d. 12/8/1850]

Westland, George (27) [mechanic; unm. d. 12/4/1853].

Westland, Margaret (24) [m. Edward Bland Atkinson, 5/3/1849; d. 6/4/1852]

Westland, Margaret (10) [m. Thomas Ferens (ex John Wickliffe); d. 27/10/1926].

Wilson, John (28) [painter]; Elizabeth née ?, wife (25).

Wilson, James (42), stonemason; Jane née ? wife (35); Thomas (18), mason; Jane (10), John (7), Isabella (5).