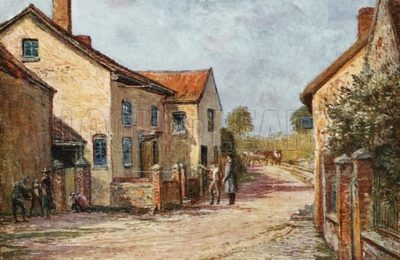

Horsleydown is an area of Bermondsey that centres around the foot of the south approach to Tower Bridge and dates back to at least medieval times. It is a name little used today and fast slipping from memory, only remembered by ancient stairs leading down to the river by Tower Bridge, by Horsleydown New Stairs next to St Saviour’s Dock and a thoroughfare called Horsleydown Lane. The area stretched from close to where Potters Fields Park is today along the river to St Saviour’s Dock land extended south roughly to where the viaduct carries the railway into London Bridge Station.

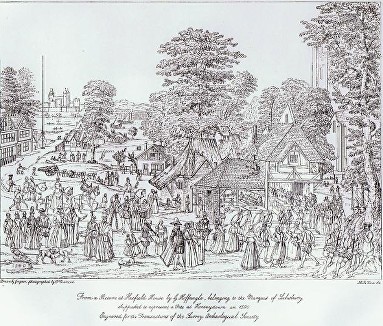

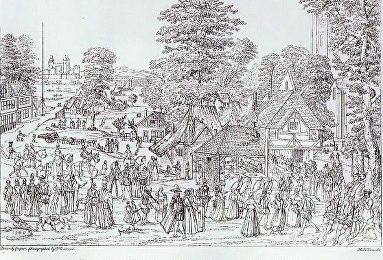

Horsleydown derives its name from Horse Down where horses were pastured, feeding on grass made lush in waterlogged fields. In the middle of the 16th century there were a few buildings and gardens leading down to the river. A fair was held and Fair Street was originally called Horsleydown Fair Street. The engraving below shows the Fair – the Tower of London shown on the left hand side on the other side of the river helps to find one’s bearings.

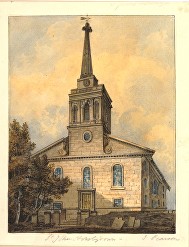

Until the beginning of the 18th century, Horsleydown was in the parish of St Olave, the church situated just by London Bridge, but the population had increased to such an extent that a new parish named St John Horsleydown was created out of the larger parish in 1726. The new church was built on a former artillery training ground and dedicated to St John the Evangelist. It was one of the churches built by the Commission for Building 50 New Churches and designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor and John James. St John’s Horsleydown was known for its rather odd spire that appeared to be an ionic column, complete with capital at the top, beneath a weather vane that incorporated a comet. Walter Besant described it as the ugliest looking church in London.

Wharves and warehouses were built along the river and in the streets beyond, and manufacturing industries appeared in the 18th century. The fields where horses once pastured and the gardens leading down to the river were built over and the area became one of the most industrial and overcrowded areas in London. Walter Besant’s book, South London, published in 1899 described the bustle of Horsleydown as

“A place of most remarkable variety as regards occupations. All along the river and the bank of the Dock, formerly Savoy [St Saviour’s] dock, there are wharves: inland are bonded warehouses, granaries, leather warehouses, hide warehouses, hop warehouses and wool warehouses. There are tanneries, currieries, fur and skin dying works, breweries, rice mills, mustard mills, pepper mills, dyeing works, dog’s food manufactories, vinegar works, bottle works, iron foundries, wooden hoop manufactories, cooperages, roperies, smithies, biscuit manufactories, oil and colour works, pin manufactories, varnish works, and distilleries. All this in a district half a mile long and a quarter of a mile broad. Between the factories and the warehouses are houses for the workmen and the foremen.”

St John’s Horsleydown was badly damaged during World War II and though a scheme was drawn up in 1956 to rebuild the church, this never went ahead and the church closed in the mid 1960s. The parish was incorporated into the parish of St Mary Magdalen, Bermondsey. The land was sold to the London City Mission who erected a new building in the 1970s using the solid foundations of the Hawksmoor and James church which rise above the ground and have been used as an integral part of the new building. The watch-house remains and is Grade II listed.

After the docks in London closed in the early 1970s, the Horsleydown area fell into a steep decline as companies either moved out or ceased trading. The area became a bleak, uncared for, deserted ghost town and a first-hand description of the impressions gained from a visit in the early 1970s can be found here. The article ends by suggesting “surely it is a possibility that there may be open space again along the Thames bank – rather in the style of the South Bank development?” And indeed, though it took many years and progress was not straight forward, this has happened. Some of the old wharves and warehouses facing onto the river were demolished and new buildings that include City Hall and More London were built on the sites. Other more solid Victorian buildings were preserved and renovated to create both residential and commercial buildings that include the former Courage Brewery and Butler’s Wharf. The expansion of the former Tooley Street recreation ground down to the river to form Potters Fields Park has created a much used open space by the river and the extension of the Thames Path, leading to Tower Bridge, has put Horsleydown on the tourist map. Though a very different area to 50 years ago and people work in shiny glass buildings rather than soot engrained warehouses, Horsleydown is once more a bustling, thriving community.

© www.exploringsouthwark.co.uk 2014-2019

Accessed at the following website.

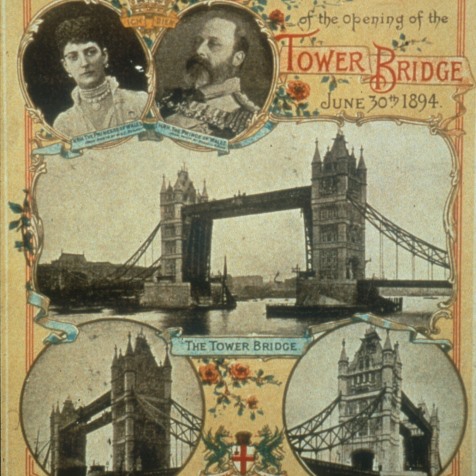

The Building of Tower Bridge

A huge challenge faced the City of London Corporation – how to build a bridge downstream from London Bridge without disrupting river traffic activities. To generate ideas, the “Special Bridge or Subway Committee” was formed in 1876, and opened the design for the new crossing to public competition.

Over 50 designs were submitted for consideration, some of which are on display at Tower Bridge. It wasn’t until October 1884 however, that Horace Jones, the City Architect, in collaboration with John Wolfe Barry, offered the chosen design for Tower Bridge as a solution.

From https://www.towerbridge.org.uk/bridge-history/

Building the Bridge

It took eight years, five major contractors and the relentless labour of 432 construction workers each day to build Tower Bridge.

Two massive piers were sunk into the river bed to support the construction and over 11,000 tons of steel provided the framework for the Towers and Walkways. This framework was clad in Cornish granite and Portland stone to protect the underlying steelwork and to give the Bridge a more pleasing appearance.

How it Works

When it was built, Tower Bridge was the largest and most sophisticated bascule bridge ever completed (“bascule” comes from the French for “see-saw”). These bascules were operated by hydraulics, using steam to power the enormous pumping engines. The energy created was stored in six massive accumulators, as soon as power was required to lift the Bridge, it was always readily available. The accumulators fed the driving engines, which drove the bascules up and down. Despite the complexity of the system, the bascules only took about a minute to raise to their maximum angle of 86 degrees.

Today, the bascules are still operated by hydraulic power, but since 1976 they have been driven by oil and electricity rather than steam. The original pumping engines, accumulators and boilers are now exhibits within Tower Bridge’s Engine Rooms.

Please Let Me Know You’ve Visited

If you have enjoyed reading this post, please leave me a comment below, even just something brief. Family history hunting can be fascinating, but often no one else is interested except the person doing the research, so it’s always really lovely to find out when someone is!

Thank you for having this interesting article up about the history of where my great-grandmother was born and lived. This article with the pictures helps make ‘history’ come alive.

I’m so glad you found it interesting and yes, I think researching the areas where our ancestors lived really helps to connect with them!

I’m trying to construct a family tree to give to my youngest daughter on her wedding day in May this year.

Family stories say that my great-great-grandfather was Captain Brown of Horsleydown. His daughter was Sarah Clara Brown, born in 1852, who married James Joseph Needham.

The story goes that Captain Brown ferried people to and from the building site when Tower Bridge was being built but I also heard that he was one of the people responsible for inventing some kind of winch, either as part of the ferry or for getting supplies up to the building site.

Do you, perhaps know anything about Captain Brown of Horsleydown?

Hi, this sounds like a great family story, but no sorry, I don’t know anything about him. It must have been a fascinating time to live in London as the bridge was being built.

Some of my ancestors lived and died in Horsleydown. I’d always pictured it as a country village which turns out to be quite wrong. My family, the Kebells, were glass blowers.

It’s fascinating when you learn a bit about an area where your ancestors lived isn’t it, it helps to bring them alive again!

I sm trying to narrow down the location of New street, Bermondsey where a few ancestors lived c1871.

I enjoyed your account very much and will keep it with me when I next go.

Keith Wilson

Hi Keith, ah I’m glad you enjoyed it. Good luck with your research!